Retrofitting Sprinklers in High-Rise Buildings: Concerns and Solutions

Owners may balk at the inconvenience and cost of retrofitting a fire sprinkler system—but there are ways to address both issues

Fire sprinklers save lives. But owners of older buildings—especially high-rise residential structures—may avoid retrofitting their properties with fire sprinkler systems due to concerns about a project’s cost and disruption. It often takes a tragic fire in a high-rise to spur local ordinances that force the issue. Even then, retrofit projects can be highly unpopular.

For example, after the deadly Midtown Towers fire in 2017, a retrofit mandate was proposed in Pittsburgh. Residents and owners of the city’s high-rises that would be affected by the ordinance raised enough opposition to delay the new law, perhaps indefinitely.

Why is there sometimes such strong resistance to fire sprinkler retrofits? For owners and residents of high-rises, a big project is synonymous with a mess, disruption to the lives of people in the building, and expense. Besides the material and labor costs, some owners may worry about a loss of income.

But retrofitting a residential high-rise with fire sprinklers doesn’t have to be this way. When owners understand their choices and the incentives for fire protection systems—and coordinate with contractors to minimize disruption—a retrofit project can be completed smoothly and economically. And the resulting system will deliver unmatched fire safety for decades.

For more information on retrofitting existing structures with fire sprinklers, read our Fire Sprinkler Retrofit Guide, just one of several guides published by NFSA. NFSA members also have access to even more educational and technical resources. Become a member or renew online today.

Balancing price and protection for fire sprinkler retrofits

They aren’t in the fire protection business, so building owners can have misconceptions about their options in a fire sprinkler retrofit. It’s important for owners to know the variations, including:

- An engineered life safety system (ELSS)

- A partial sprinkler system

- A sprinkler system compliant with NFPA 13: Standard for the Installation of Sprinkler Systems

Owners should communicate with designers, contractors, and AHJs to understand the safety and price tradeoffs involved with each. But in the end, nothing compares with the protection of a complete NFPA 13 sprinkler system.

Engineered life safety systems may be an option, but they’re not equivalent to sprinklers

The engineered life safety system (ELSS) is a feature of NFPA 101: Life Safety Code. An ELSS, which is designed by a registered professional engineer and approved by the AHJ, is really a combination of fire protection systems that might include some combination of partial sprinkler coverage, detection equipment, smoke control measures, and compartmentation.

NFPA 101 allows an ELSS to be used as an alternative to a sprinkler system:

From the 2018 edition of NFPA 101 (Existing Apartment Occupancies)

31.3.5.12.3* An automatic sprinkler system shall not be required in buildings having an approved, engineered life safety system in accordance with 31.3.5.12.4.

It also gives the option (39.4.2.1) to install an ELSS in lieu of a sprinkler system in existing business occupancies.

Local laws may let owners choose them instead of sprinkler systems, as well. Honolulu’s 2018 retrofit requirement offers owners the ELSS option (though, without explicitly calling it such). The law requires owners to undergo and pass evaluations regarding the safety of their building—systems like smoke control, smoke detection, elevators, emergency lighting, and more—if they don’t install sprinklers.

Property owners may gravitate toward an ELSS as a lower-cost, lower-disruption alternative to sprinklers. But an ELSS can never provide the same protection as a sprinkler system. Owners need to understand that only fire sprinkler systems prevent flashover, the total involvement of a space in a fire. This phenomenon can happen in minutes, and no one survives in an area that experiences it. Different components of an ELSS may sound the alarm or limit a fire to a specific area, but they can’t stop flashover.

Watch (and share!) this demonstration of how flashover can completely ignite a room:

To make the best financial and safety choice, the stakeholders should understand their fire protection needs and the capabilities of the systems that address them. A full sprinkler system can cost more up-front than an ELSS, but that investment provides active protection for life and property.

Partial systems may be allowed—as part of an ELSS or not—but they also only provide partial safety

Building owners sometimes avoid fire sprinkler retrofits because they perceive them as an all-or-nothing proposition. And “nothing” may appear to be the economical choice— until tragedy forces an installation.

Besides a complete NFPA 13 system or an ELSS, there is sometimes a middle ground—a partial sprinkler system. Los Angeles’ Dorothy-Mae ordinance (named for the 1982 high-rise fire that killed 24 people), for example, requires a partial system with sprinklers placed in corridors above apartment doors in pre-1943 buildings with three or more stories.

Even when partial sprinkler systems aren’t written into local code, designers and building owners may be able to work with AHJs to get permits. This is especially true with voluntary fire sprinkler retrofits. The Viking Automatic Sprinkler Company built something similar to a Dorothy-Mae system for the St. Clair Apartments in Portland, OR. Pipe was run down corridors, and a sprinkler was placed over the door of each apartment. Local officials assisted Viking with both the system design and the appeal process with the building office.

As with an ELSS, AHJs, owners, and contractors need to weigh their options. And an ELSS may or may not include partial sprinkler coverage. Nevertheless, a complete fire sprinkler system provides the most protection. Thus, how much tradeoff is acceptable?

Looking beyond sticker price—fire sprinkler retrofits are an investment

A fire sprinkler system is a valuable investment in a property, and this value extends far beyond the cost of materials, labor, and an added amenity. As NFSA’s former Vice-President of Engineering Kenneth Isman explains, building owners should look beyond the initial price to retrofit a system and consider factors like insurance, liability protection, and business continuity, not to mention potential tax incentives.

Consider the example of the Marco Polo high-rise condominium in Honolulu. The structure experienced a fire that caused $1.1 million in damages in 2013. Shortly afterward, the building association received an estimate for a sprinkler retrofit. It would have cost $4.5 million, and they opted not to install a system.

That choice proved to be uneconomical, as well as tragic. In 2017, another fire caused more than $100 million in damages and killed four Marco Polo residents. The owners also faced lawsuits from the victims’ families that alleged a failure to ensure safety—and the complainants received payouts of undisclosed sizes. This fire spurred Honolulu’s fire sprinkler retrofit ordinance, and Marco Polo ended up installing a sprinkler system that cost $5 million.

Insurance

Insurance companies love fire sprinklers—they know they will pay out significantly less in damages in the event of a fire. That’s why owners can earn significant policy discounts by retrofitting their buildings with sprinklers. The insurance savings can pay for the cost of the system in a matter of years.

In 2010, Isman estimated that a 20-story 257,000 ft.2 hotel would cost about $800,000 to retrofit with sprinklers (assuming a retrofit cost of $3/ft.2). If that building were insured at a value of $40 million, and its contents were covered at a value of $5 million, the owners could save in the neighborhood of $78,000 in annual insurance payments by adding sprinklers.

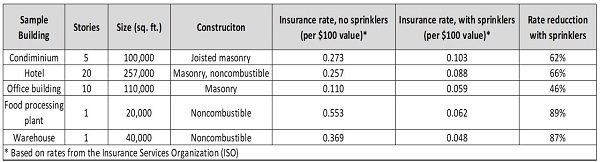

The insurance savings alone can be considerable. These figures come from Kenneth Isman’s evaluation of the financial benefits of sprinkler retrofits and are based on rates from the Insurance Services Office.

Liability protection

Fire sprinklers also offer protection against liability. Even though local codes may not require existing structures to be retrofitted with sprinklers, building owners can still face lawsuits because fire sprinkler systems can be considered what is expected as reasonable care for occupants and residents.

As mentioned, the families of the victims of the Marco Polo disaster successfully sued and settled with the building owners. They alleged in their lawsuit that the owners chose not to implement safety features that could have saved lives. The fact that sprinklers weren’t required by law at the time did not matter—the settlement involved payouts of an undisclosed sum to the estates of the victims.

Tenants of Barrington Plaza, a Los Angeles high-rise apartment building that burned in January 2020, have initiated a class-action lawsuit against the owners, accusing them of negligence. The building did not have sprinklers. This omission was despite the fact that Barrington Plaza previously experienced a fire in 2013, and the owners were sued for negligence in 2014—over, among other things, a lack of sprinklers.

Minimize losses, ensure continuous business operations

Fire sprinkler retrofits can significantly reduce losses and enable operations (and thus income) to return to normal quickly after a fire.

When a building burns, flames and toxic smoke cause direct damage to the property—and the longer a fire burns, of course, the more damage accrues. The high volume of water used by firefighters to put out a blaze also causes serious damage that can seep far beyond the burn area. And after a fire, lost income from rent or business is added to the repair expenses.

Fire sprinklers vastly minimize losses by keeping fires small or putting them out altogether. Small blazes cause less direct burn damage and fewer business interruptions and require far less water to extinguish. The volume of water sprayed by a sprinkler can seem like a lot, but the 8-24 gallons per minute issued from a quick-response sprinkler head is nothing compared to the 80-125 gpm that a fire hose puts out.

As a fire grows, the amount of water needed to fight it vastly increases. Stopping a blaze early with a sprinkler causes some water damage, but it’s far better than the alternative—by a long shot.

How long does it take to retrofit a building? And how much will it disturb occupants?

Building owners and residents wonder how long the process will take and what it will mean for their everyday lives. In business settings, disrupting operations for a retrofit can mean productivity losses. In residential environments, tenants worry about the mess and stress of renovation. Will they have to move out? Owners of apartment buildings stress about losing rent and the expense of housing their residents elsewhere.

Retrofitting large high-rises with fire sprinklers can take a year or more, depending on conditions. This doesn’t mean that the whole building is disturbed for a year, however. A sprinkler retrofit project doesn’t have to upend everything. With careful planning, cleanliness, and communication, sprinkler contractors and owners can minimize the disruption, even when challenges like asbestos are encountered.

Scheduling and communication smooth the process

The 2014 sprinkler installation at Saligman House, a 10-story 123,000 ft.2 apartment complex with 180 units located in Philadelphia, offers an excellent example of a retrofit done right. The project took 11 months to complete—but residents were only briefly disturbed and never had to move out.

This was possible because of careful planning and scheduling. The sprinkler contractor worked closely with a general contractor performing other renovations to schedule work in no more than five apartments per day. Work was completed during business hours, and those residents who weren’t at work were accommodated by the owners. Building personnel set up a day room with resources to help residents get through the day without having to go back up to their unit for medications, phone calls, etc. The retrofit was also scheduled to give plenty of time for cleanup of individual units so that occupants could sleep in their beds each night.

Nondestructive installation minimizes mess and avoids full asbestos abatement

Cutting into walls and ceilings to hang pipe is always somewhat disruptive and dirty. But when asbestos is involved, the hazard makes work much more complicated, and residents may have to relocate. Many buildings built before sprinkler requirements were also put up before the ban on asbestos. Owners may believe that they have to fully abate the asbestos to install sprinklers, causing them to avoid a project.

But full asbestos abatement is often unnecessary. Spot abatement, or the targeted removal of asbestos as required, can keep prices down while preserving safety. Complete asbestos abatement can cost between $15 and $20 per ft.2 in Los Angeles, for example. But spot abatement may only add about $1–$4 per ft.2 to a project.

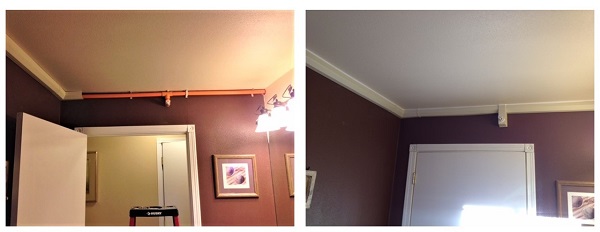

Nondestructive installation can also reduce mess, workload, and asbestos concerns. One useful nondestructive technique involves concealing pipe with a decorative soffit instead of placing it inside the ceiling. Soffits allow contractors to avoid cutting into surfaces while still maintaining an attractive look.

Asbestos was discovered in the ceilings of the Saligman House. To avoid full abatement, the contractors hung pipe from the concrete brick walls rather than the ceiling and hid the pipe with soffits.

A soffit is a decorative housing that can be used to conceal pipe or other utilities. At Saligman House, a soffit, similar to the one shown here, was used to hide the sprinkler pipe. This saved the workmen from having to cut and patch the ceiling and abate the asbestos. Source: DecoShield

Retrofitting a high rise with fire sprinklers doesn’t have to be a headache—and it’s an investment with invaluable ROI

Fire sprinklers save lives and can avoid immense property damage and follow-on costs. Nevertheless, retrofitting existing structures with sprinklers is often viewed as an overly expensive and complicated proposition. But with good planning and communication by all of the stakeholders, the process can go smoothly and make business sense.

When owners know their options, they can make the best possible choices. And nothing provides better protection than a complete fire sprinkler system.

Between the increased insurance payments, the interruption of business, and potential lawsuits after a fire, failing to retrofit a building can cost a lot of money in the long run. And when contractors and owners plan and communicate, a sprinkler retrofit project doesn’t have to involve major shutdowns—even if obstacles like asbestos are encountered.

For more information about fire sprinkler retrofit projects, read our Fire Sprinkler Retrofit Guide. NFSA also has guides on the benefits of fire sprinkler systems, a comparison of sprinklers and ELSS, and recent changes to model codes.

VIEW ALL NFSA FIRE PROTECTION GUIDES

For over a century, the National Fire Sprinkler Association (NFSA) has served as the voice of the fire sprinkler industry. Our mission: advocating to protect lives and property through the widespread acceptance of the fire sprinkler concept. To join NFSA or learn more about the ways membership can benefit your organization, visit nfsa.org/join.