ICC and NFPA Updates that Impact Fire Sprinkler Installations

Read our guide to some upcoming 2021 model code changes—and learn how to use the latest edition of NFPA 13

2020 fire protection requirements look drastically different than those in the first model codes that debuted more than a century ago. Early code makers never could have envisioned the need for rules that address the potential for runaway fires in energy storage systems, the fire risk posed by modern construction materials, food truck safety, or a burgeoning legal cannabis industry.

Fortunately, codes are “living” documents—continuously updated to adapt to an ever-changing world and keep people safe. For 2021, the International Code Council (ICC) and the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) will release a new round of essential model codes.

In this blog, we provide a summary of the codes that will update their NFPA 13: Standard for the Installation of Sprinkler Systems references to the 2019 edition of that vital standard. We also compile some key changes that impact sprinkler installations so contractors won’t be surprised by what’s different.

Finally, we help installers understand the most significant revisions in the latest edition of NFPA 13, including how to navigate its significant reorganization from the previous version.

How new model codes will impact 2020 fire protection

The 2021 editions of several ICC and NFPA model codes are slated to arrive between late summer and fall of 2020. Every model code references various organizations’ standards within its requirements. Once a new version is adopted by an authority having jurisdiction (AHJ), these referenced standards become a legally enforceable part of the code.

That means sprinkler contractors must understand what the reference requires, how those requirements need to be applied, and who is responsible for ensuring compliance. Specifically, if you’re an installer, it’s your responsibility to ensure that your project complies with all relevant requirements in the referenced codes and standards, which can even include manufacturers’ installation instructions.

The following 2021 ICC and NFPA codes will update their NFPA 13 references to the 2019 edition. We’ve outlined some critical revisions to these documents that will impact sprinkler installations:

2021 International Building Code (IBC)

- Open parking garages. This change eliminates the blanket exception for fire sprinklers in open parking garages in IBC. Instead, it provides two new thresholds to trigger fire sprinkler requirements: new open parking garages over 55 feet in height or new open parking garages over 48,000 square feet in fire area.

- Pedestal buildings and standalone residential buildings protected by NFPA 13R: Standard for the Installation of Sprinkler Systems in Low-Rise Residential Occupancies. This change will limit NFPA 13R systems to buildings with three stories rather than four.

2021 International Fire Code (IFC)

- High-rise retrofits. This change adds language in IFC Chapter 11 that requires existing high-rise buildings over 120’ to retrofit with fire sprinklers. High-rises less than 120’ (to 75’) have the option to provide a second stairway, a full fire alarm system, or a retrofit with fire sprinklers.

- High-piled storage frequency inspections. This change adds text to IFC that requires an annual nine-point inspection of high-piled storage buildings to maintain the approved storage arrangement, commodities, and fire protection.

2021 International Existing Building Code (IEBC)

- Scope. Changes to the scope of IEBC recognize that IFC’s Chapter 11 retrofit requirements need to occur before applying IEBC.

- Alterations. Changes increase the threshold for fire sprinkler systems in IEBC when the level of alterations to a property is increased.

2021 International Residential Code (IRC)

- IRC P2904 and NFPA 13D correlation. Several changes update IRC P2904 fire sprinkler installation requirements to correlate with the 2019 edition of NFPA 13D: Standard for the Installation of Sprinkler Systems in One- and Two-Family Dwellings and Manufactured Homes. Freeze protection, ceiling configuration, water meter tables, and more were updated for parity between the two documents.

- More (but not complete) clarity. Townhouse units are defined. Clarification is given that sprinklers are required when habitable attics are utilized. While sprinklers are mandated throughout IRC, more clarity is still needed for sprinklers when states remove the requirements.

2021 NFPA 1: Fire Code

- Extract material. A re-evaluation of extracted sections of other standards in NFPA 1—such as NFPA 13 and NFPA 25: Standard for the Inspection, Testing, and Maintenance of Water-Based Fire Protection Systems—to provide a one-book resource.

2021 NFPA 101: Life Safety Code

- Electric supervision. Changes clarify and correlate the terminology of fire sprinkler supervision requirements.

- ELSS. This change increases the qualifications for initiating an Engineered Life Safety System (ELSS) in NFPA 101 over retrofitting sprinklers in existing high-rise residential chapters. The National Fire Sprinkler Association (NFSA) offers a new guide, “Engineered Life Safety Systems: An Examination of the Concept,” to provide fire officials with background information and suggested criteria for approving or disapproving alternative systems during sprinkler retrofit programs.

2021 NFPA 5000: Building Construction and Safety Code

- Electric supervision. Changes clarify and correlate the terminology of fire sprinkler supervision requirements.

- One- and two-family homes. Changes correlate NFPA 5000’s one- and two-family home sprinkler tradeoff requirements to the IRC.

NFPA updates: Tips for navigating the 2019 overhaul of NFPA 13

Since 1896, NFPA 13 has offered guidance to sprinkler system installers, addressing everything from technological innovations to best practices for system design. But as the standard grew in scope and scale through more than 60 editions, it became increasingly difficult for users to manage and follow. Redundancies also crept in, creating more confusion and increasing its size to nearly 500 pages.

By 2016, NFPA 13 was pretty comprehensive—but the committees acknowledged it was time for a big-picture makeover. The resulting, significant changes to the 2019 edition of NFPA 13 were carefully designed to make the document more accessible. If your jurisdiction adopts code that requires you to use the latest version, here’s how to navigate its dramatic reorganization:

How to use NFPA 13’s designer-friendly sequence of topics

Information in NFPA 13 is now clearly separated by subject matter, from sprinkler technology to storage method. After defining key terms and introducing general requirements, the 2019 edition also adds a designer-friendly sequence of topics.

Put simply, that means information is logically organized in the order it’s needed by anyone planning a sprinkler system installation. For instance, Chapter 5 now includes requirements for a water supply, one of the first considerations for a sprinkler installation. Previously, the water supply wasn’t addressed until Chapter 24, forcing designers and engineers to flip back and forth to reference information.

From there, the 2019 edition continues with underground piping, system types, and sprinkler placement. It then moves on to installation requirements for sprinkler heads, valves, and system piping. Finally, it wraps up with special requirements, working plans, and system acceptance requirements.

An essential component of the NFPA 13 overhaul involves changes to Chapter 8, which previously functioned as a “junk drawer” of sorts for installation requirements. The 2019 edition spreads those requirements out across multiple chapters, making it simple for installers to quickly locate the information they need.

NFPA 13’s latest edition also simplifies the organization of storage sprinkler requirements. Previously, these mandates were scattered throughout 10 chapters and organized by the type of material stored and the method used to store it. The new edition sequences these requirements into six chapters ordered mainly by sprinkler type.

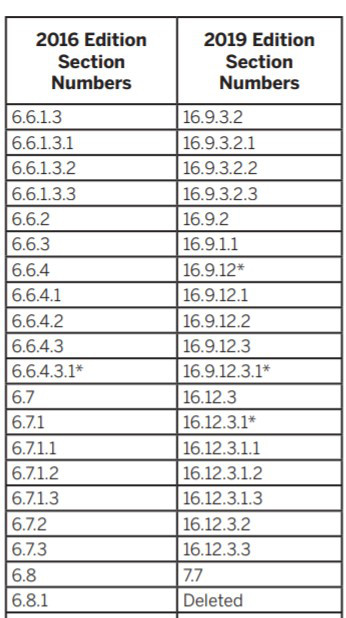

NFPA 13’s Roadmap makes it easy for users to find what they need by matching 2019 sections with the old 2016 edition section numbers. Source: NFPA 13

2020 fire protection made easy with the 2016-2019 Roadmap

Of course, while NFPA 13’s makeover was designed to be practical, it may take some getting used to by long-time readers of previous editions. To ease the transition, the 2019 edition features a new series of tables dubbed the “2016-2019 Roadmap.” Located just after the index (page 544 in the PDF version), this 26-page section helps readers find what they need by matching 2019 references with their old 2016-edition section numbers.

The roadmap creates a quick-reference locator by listing each section from the 2016 edition in the original sequence, and then pairing it with its new 2019 number. For example, those looking to view requirements for installing standard pendent and upright spray sprinklers—formerly located in section 8.6—are sent to section 10.2 of the 2019 edition.

The roadmap also indicates when a section has been merged, deleted, or spread across multiple chapters.

Recognizing NFPA updates and revisions in the 2019 code

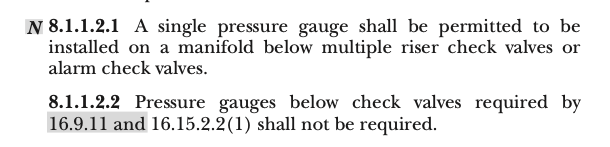

To ensure new or revised requirements stand out, the 2019 edition shades revised text and marks new mandates with the letter “N.” For instance, the requirement for listings of fire sprinkler system components and hardware no longer includes drain piping, drain valves, and signs as examples of unlisted equipment. Instead, these examples have moved to the annex, where a new section explains NFPA’s reasoning for the requirement and adds a few new examples.

To highlight changes, the 2019 edition of NFPA 13 shades revised text and marks new rules with the letter “N.”

Other key changes to the 2019 edition of NFPA 13

The NFPA 13 Technical Committees made a conscious decision to focus the majority of changes on reorganizing the standard. But there are a handful of significant technical updates that sprinkler installers should note:

NFPA updates NFPA 13’s alignment with residential standards

Perhaps the most important technical revisions improved synergies between the 2019 editions of NFPA 13 and NFPA 13R. NFPA 13R governs low-rise residential occupancies, but many multi-story residential buildings, nursing homes, and larger residential occupancies must follow NFPA 13 instead. In fact, some jurisdictions require NFPA 13 even if NFPA 13R applies, due to the former’s greater emphasis on property protection.

A key change set forth by section 16.3.9.6.2 in the 2019 edition explicitly allows the use of thermoplastic pipe in sprinkler systems installed in private garages within some residential buildings covered by NFPA 13. NFPA 13 classifies automobile parking and showrooms as Group 1 Ordinary Hazard, but NFPA 13R specifically exempts certain private garages from those stricter requirements.

The new code aligns NFPA 13 with NFPA 13R as well as IBC requirements. It treats residential garages as part of the dwelling unit instead of a separate occupancy subject to stricter standards, including the use of metallic piping.

The 2019 edition of NFPA 13 permits residential fire sprinklers near beams and under sloped surfaces, if certain conditions are met.

Sections 12.1.1 and 12.1.8.1 offer another important change that deepens NFPA 13’s alignment with the residential standard. The new sections enable installers to place pendent and upright residential fire sprinklers near beams and under beamed and sloped surfaces in NFPA 13 systems when certain conditions are met. Concealed sprinklers are held to a stricter standard (12.1.8.1.3).

12.1.1 transplants its sprinkler design criteria from NFPA 13R, offering basic requirements for residential sprinklers by ceiling and sprinkler type. A.12.1.1 explains that extensive fire testing has shown that listed, properly placed residential sprinkler heads can effectively fight fires in these environments.

Automatic control valves are permitted

Section 16.9.4 introduces automatic control and indicating valves to NFPA 13. The addition paves the way for installers to use these new technologies in compliant fire sprinkler systems.

In rare instances when sprinkler systems fail to operate as expected, improperly closed control valves are a primary reason. Note that NFPA 25: Standard for the Inspection, Testing, and Maintenance of Water-Based Fire Protection Systems permitted automated inspection and testing of sprinkler systems for the first time in its 2017 edition. These changes make it easier to test system components more frequently and trigger a supervisory alert if results are off.

Relaxed and revised requirements for ESFR sprinklers

Other noteworthy changes to NFPA 13’s 2019 edition allow for the installation of early suppression fast response (ESFR) fire sprinklers under obstructed combustible construction. In previous versions, ESFR use was limited to unobstructed and noncombustible spaces. This revision, stated in section 14.2.4, aligns NFPA 13 with guidelines from FM Global and manufacturers’ findings on the suitability of ESFR sprinklers for use around bar joists, beams, and girders.

Section 23.7.4.1 adds a new limit to ESFR sprinklers covering exposed expanded Group A plastics. These materials, which range from mattresses to foam plastic containers, incite dangerously hot, hard-to-fight fires that can quickly spiral out of control. While changes that allowed ESFR sprinklers to be installed as low as 18 inches from the ceiling were considered for fighting these fires, the final revision settled on a 14-inch deflector-to-ceiling limit.

Criteria for 25.2 K-factor sprinklers and spacing guidelines for in-rack storage sprinklers

Some situations—such as some Group A plastics and Class I through Class IV commodities—require greater protection than an overhead sprinkler system can provide on its own. In-rack sprinklers, along with horizontal barriers, can provide that extra level of safety.

Using criteria based on full-scale fire tests, section 25.8.3 adds installation requirements for pendent in-rack sprinklers with a 25.2 K-factor—the largest orifice size yet.

Section 25.5.2 also updates horizontal spacing requirements for in-rack sprinklers. In some cases, it expands the 8’ limit recommended in the 2016 edition. This change clarifies existing guidelines, which already seemed to permit 10’ spacing on some sprinklers in longitudinal flue spaces (the area between commodities on back-to-back racks). But keep this in mind: sections throughout the 2019 edition still require 8’ spacing across the width for racks with multiple rows.

The 2019 edition of NFPA 13 updates tables specifying the maximum load of wedge anchors in pipe-hanging applications.

Updated tables for CMSA sprinklers and wedge anchors

When facing extreme fire hazards, control mode specific application (CMSA) sprinklers produce large droplets at low pressures for improved fire penetration and control. Full-scale fire tests of CMSA sprinklers show that 25.2 K-factor heads are suitable for protecting palletized and solid-piled storage of Class I through Class IV commodities. Changes to tables 22.2 through 22.5 in the latest edition of NFPA 13 emerged from this new listing data. The revised tables offer additional design criteria for CMSA sprinklers in storage applications.

Other tables in the 2019 edition of NFPA 13 have also been revised, including those specifying the maximum load of wedge anchors in pipe-hanging applications. New criteria were put in place when NFPA issued a tentative interim amendment (TIA) roughly two years before the 2019 edition was released. The tables in section 18.5 align NFPA 13 with recent standards from the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE).

Common-sense practices for air compressors in dry sprinkler systems

Section 8.2.6.6.5 states that where air compressors serving dry sprinkler systems are permanently installed, they must be installed in compliance with the requirements of NFPA 70: National Electrical Code. The revised code adds that a general-use light switch or cord-and-plug-connected motor can’t be used as the disconnecting means.

While the use of light switches and cord-and-plug-connected motors work in many applications, a flipped switch or pulled plug can trigger an accidental decline in pressure in a dry system—leading to false trips. Electricians or system installers repairing compressors also can’t correctly lock and tag them if they are disconnected by a “general-use light switch.”

A new exemption for concealed combustible spaces

Under some circumstances, NFPA standards permit sprinkler designers to leave certain parts of a space unprotected, usually for practical reasons. Many of these areas are concealed spaces created by building construction, such as the space between a ceiling and a rooftop. Section 19.3.3.1.5.2 expands NFPA 13’s list of exemptions for minimum sprinkler operation in combustible concealed spaces. It clarified that wall cavities created where drywall or other wall material attaches to wooden studs are not required to be protected with sprinklers.

Formalized requirements for working plans

Previous editions of NFPA 13 required the submission of sprinkler designs to fire authorities, and even provided a detailed list of items to include. But they offered no official minimum requirements.

In the 2019 edition, section 27.1 clarifies the minimum requirements for working plan submittals. It also updates the 46-item (now 47-item) list guiding the development of working plans.

A key change was aimed at helping reviewers guarantee the accuracy of seismic calculations—”zones of influence used in calculations for seismic bracing [must be] indicated on working plans” (42). The new rules also ensure that plans include the “make, type, model, and size of [a] backflow prevention assembly” often needed for NFPA 13 systems, and “[the] means to forward flow test at these assemblies at system demand” (25).

The 2019 edition of NFPA 13 is a more user-friendly tool for sprinkler installers.

Getting up to speed on 2021 ICC and NFPA updates—and applying NFPA 13 correctly—doesn’t have to be a Herculean task

With so many model codes updating at once, keeping current can feel daunting. Our review of 2021 ICC and NFPA updates that impact NFPA 13 sprinkler installations should make it easier to learn what’s new—though, we’ll have additional summaries of the revisions as the documents are released.

A fundamental change is that many of the new model codes call for referencing the 2019 edition of NFPA 13. While the latest installation standard looks dramatically different than previous versions, its navigation offers serious benefits for fire sprinkler professionals—it’s a clearer, more concise document.

Want to stay up-to-date on new codes and standards? NFSA offers training, blogs, and expert resources to keep you informed.

For over a century, the National Fire Sprinkler Association (NFSA) has served as the voice of the fire sprinkler industry. Our mission: advocating to protect lives and property through the widespread acceptance of the fire sprinkler concept. To join NFSA or learn more about the ways membership can benefit your organization, visit nfsa.org/join.